Background

My twitter feed is becoming more and more (pure) FP oriented. Many of the people I follow from the Scala community are advocating for Haskell over Scala lately. To be honest, I was always intrigued about pure FP, but never got to use it in the “real world”1. I always worked in teams that had OOP mindset, and codebase. With Scala I was able to shift the balance a little bit towards FP. I advocated for referential transparency, strongly typed over stringly typed code, higher order functions, higher kinded types, typeclasses, etc’… I aimed to be more FP in an OO world. But I never managed to get my peers into learning together, and using, “pure FP” with libraries like cats or scalaz. So I wonder, does pure FP really is the answer - the silver bullet - I’m looking for, or should we tilt the balance less towards purity in Scala?

Harsh criticism against impure Scala

In the latest scalapeno conference, I attended John De Goes’ keynote “The Last Hope for Scala’s Infinity War”. In the talk, John claimed that: > “Some of the proposed features in Scala 3 are targeting someone who doesn’t exist”

He referred to features like Type Classes & Effect System.

But the truth is, that john was wrong. There is at least one person that wants such features2. There is a middle-ground. And I want to believe I’m not alone, and some other people see the value Scala has to offer for FP lovers (wannabes?) working with traditional OO programmers, trying to make a difference.

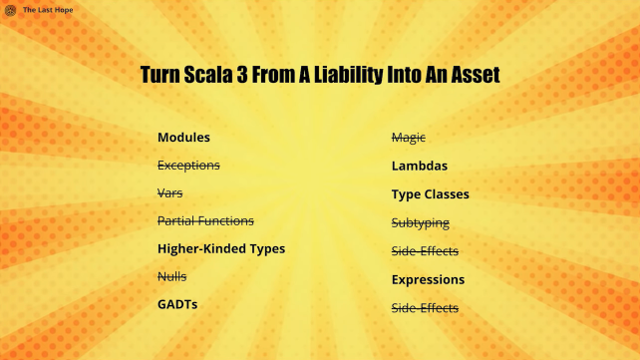

Like John, I love Scala. but unlike John, I don’t think we need to

And I don’t want to see all the crossed out features removed from Scala:

Scala is expressive

I was recently asked, why I love Scala. I answered that with Scala, It’s very easy for me to express exactly what I mean for the program to do, and that it’s easy to expose beautiful (and safe) functional interface, while encapsulating impure logic and gaining the benefit of both worlds. I was then asked to give an example, of short code that I find easy to express in Scala, and hard(er) to write in other languages. I choose something I’ve written a while ago, and I find as a nice example for such FP-ish pattern.

def mapr[A,B](as: Vector[A])

(f: A => Future[B])

(g: (B,B) => Future[B]): Future[B]So… what’s so special about mapr? A quick scala thinker will implement it with something like3:

Future.traverse(as)(f)

.flatMap(_ reduce g) // if g were (B,B) => BAnd it can be fine, considering the usecase. It wasn’t fine in our case.

The “real world” case

Consider A to be file names to fetch from a S3 bucket. But not just any file, it’s a CSV with time series events. B is a time based aggregated states series of the events. f can be “fetch & aggregate” a single file. But since many “sources” (S3 files) can add data, we should think about merging (reducing) multiple sources into one uber states series4. Thus we need g to “merge” two time based aggregated states into a single time based state series. Now, file sizes range from a few MBs, up to ~10GB. And this is important, because in the simple solution, we cannot start reduce-ing the small files, until we are done fetching and transforming the bigger 10GB files. Also, if the first A in the Vector is also mapped to the heaviest B, the reduce will be expansive since we always merging ~10GB B.

Lawful properties

In this case, there are interesting things to note about g5:

gis assocciative, it doesn’t matter how we group and merge two time based series states.gis commutative, order is irrelevant. switch LHS with RHS, and get exactly the same result.

So now, our random pure-FP dude might say: great! your category B sounds very similar to a semilattice. Let’s also prove that g abides the idempotency law, and that g(b,b) == b for any \(b\), and maybe we’ll find a useful abstraction using semilattice properties.

Well, that FP-programmer is actually right. and all that high gibberish talk actually has solid foundations. And in fact, that function g over B I just described does define a semilattice. Bs has partial ordering6, g acts as the “join” operation, and we even have an identity element (the empty time series), so it is even a “Bounded Semilattice”.

But this is totally irrelevant and out of the question’s scope. Remember, we are working in an OO organization. If we start defining abstractions over semilattices (or maybe there are ones in cats or scalaz libraries? I really don’t know), The code will become one giant pile of gibberish in the eyes of my coworkers. And we don’t even need it. What is needed, with the realization that g is associative & commutative, is a very natural optimization that pops to mind: why wait for all A => B transformations? whenever 2 Bs are ready, any 2 Bs, we can immediately apply g and start the merge process.

So, without over abstracting, I came up with the following piece of code (brace yourselves):

def unorderedMapReduce[A, B](as: Vector[A])

(f: A => Future[B], g: (B,B) => Future[B])

(implicit executor: ExecutionContext): Future[B] = {

val promises = Array.fill(2 * in.size - 1)(Promise.apply[B])

var i = 0 // used for iteration optimization

// (not needing to search for uncompleted

// promise from start every time)

def completeNext(tb: Try[B]): Unit = tb match {

case Failure(e) => promises.last.tryFailure(e) // fail fast

case Success(b) =>

// We're not synchronizing i, since we can guarantee we'll always

// get an i that is less than or equal to latest i written by any

// other thread. But we cannot use i += 1 inside the loop,

// since it may result with skipping a cell in 2 threads doing

// the increment in parallel, so each thread get's an initial copy

// of i as j, and only increment it's own copy. eventually,

// we replace i with a valid value j (less than or equal to

// first not used promise)

var j = i

var p = promises(j)

while ((p eq null) || !p.trySuccess(b)) {

j += 1

p = promises(j)

}

i = j

}

as.foreach { a =>

f(a).onComplete(completeNext)

}

promises

.init

.zipWithIndex

.sliding(2,2)

.toSeq

.foreach { twoElems =>

val (p1, i1) = twoElems.head

val (p2, i2) = twoElems.last

// andThen side effect is meant to release potentially heavy

// elements that otherwise may stay for potentially long time

val f1 = p1.future.andThen { case _ => promises(i1) = null }

val f2 = p2.future.andThen { case _ => promises(i2) = null }

failFastZip(f1,f2)

.flatMap(g.tupled)

.onComplete(completeNext)

}

promises.last.future

}

// regular Future.zip flatMaps first future, so it won't

// fail fast when 2nd RHS future completes first as failure.

def failFastZip[A,B](l: Future[A], r: Future[B])

(implicit executor: ExecutionContext): Future[(A,B)] = {

val p = Promise[(A,B)]()

l.onComplete(_.failed.foreach(p.tryFailure))

r.onComplete(_.failed.foreach(p.tryFailure))

for {

a <- l

b <- r

} p.success(a -> b)

p.future

}I can imagine the horror on the face of our random FP-dude, an Array (mutable), vars, nulls, side effects,… OMG. John would not approve such abomination. But before you panic, bare with me and let’s break it down.

The what & how

The goal is to have a “bucket” of ready B elements, and whenever we have 2 or more Bs in the “bucket”, we take a pair out of the bucket, compute g on it, and when g returns with a new B, we put it right back in the “bucket”, and we continue to do so, until only a single finite B element is left in the bucket. this is our return value.

The way it is done, is simple. we have \(n\) A elements in the original sequence, each will be mapped to a single B, and since every 2 Bs are used to generate a new B, we need room for another \(n-1\) Bs in the bucket. Overall, \(2n-1\) elements, and our “bucket” can be just a simple Array. We also want to parallelize the computation as much as we can, so some construct to handle the asynchronous nature of the computation is needed. I used a Promise[B] to store the result. So our “bucket” is simply an Array[Promise[B]] of size \(2n-1\).

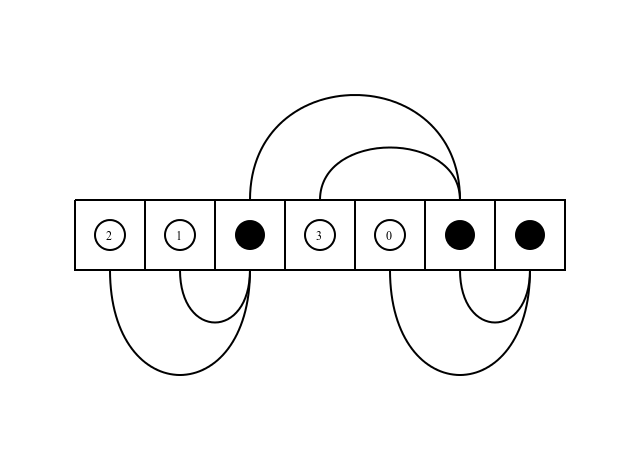

Have a look at the following figure:  This illustrates the order of computation, when the order is:

This illustrates the order of computation, when the order is:

- as(2)

- as(1)

- g(as(2),as(1))

- as(3)

- as(0)

- g(g(as(2),as(1)),as(3))

- g(as(0),g(g(as(2),as(1)),as(3)))

In the simple FP approach (traverse + reduce), same execution will result with the following computation order:

- as(2)

- as(1)

- as(3)

- as(0)

- g(as(0,as(1))

- g(g(as(0,as(1)),as(2))

- g(g(g(as(0,as(1)),as(2)),as(3))

Which means we don’t take advantage of the early completed computations.

More benefits

Using early completed computations isn’t the only reason I argue the suggested code is superior. It’s not just we start computations eagerly, implicitly it also means that heavy elements are left to be dealt in in the end, and we don’t need to reduce 10GB files at every step of the way7. We also get “fail fast” semantics; for example, if g fails for whatever reason on as(2) input, in the code I suggest, you fail fast since it is mapped directly as a failed Future result. Also, whenever a future completes, we have a side effect to clean up values that are not needed anymore, so we don’t leak.

Bottom line

What I try to emphasize using the example I showed, is that there are good reasons to write impure functional code. In cases like this, you enjoy both worlds. The interface is functional, it is referential transparent (as much as Future is considered referential transparent). Perhaps the above is achievable using pure functional style (I would love to know how. really!), but my gut is telling me it won’t be so simple. And as someone who works mostly in hybrid FP-OO teams, I can’t go full FP. Not at first anyway… Using Scala enables me to introduce a smoother transition into FP without getting my peers too angry or confused. It enables me to break the rules if I really need to. I wouldn’t sacrifice the impure parts of the language. I truly think they are too valuable.

You are reading that person’s blog. Obviously :)↩︎

Actually, I’d bet he would use

TraversableandTaskover std lib’sFuture.traverse↩︎There are multiple ways to approach that problem, and actually, we ended up with another solution, that utilized akka-streams, merging multiple sources with a custom stage &

scaning to output a stream of aggregated state in time order.↩︎Whenever I encounter such realization, I automatically translate it to property checks tests. So to test that

gis lawful, all I needed is a very simple scalacheck test to test associativity & commutativity.↩︎think about

b1 != b2, which means that eitherg(b1,b2) > b1and alsog(b1,b2) > b2, or thatb1andb2already has order relation between them. It may be more obvious in some situations (and it was obvious in our case).↩︎Kind of reminds me of the matrix chain multiplication problem.↩︎

No comments:

Post a Comment